Amazon’s Cloud Drive: Convenience — and Controversy

Late last month, Amazon, the Seattle-based online retailing giant, announced the premiere of its Cloud Drive, an online music-backup service that allows Amazon customers to store music “in the cloud,” with the ability to access personal libraries from any location and on any computer. While putting Amazon in the pole position ahead of Apple and Google — which have both been working to bring to market similar cloud-based ventures — the announcement touched a nerve within the music establishment, as labels and publishing executives appeared ready to challenge the legality of Amazon’s arrangement.

License, Please?

Amazon spokesperson Cat Griffin put it bluntly: “We do not need a license to make Cloud Player available.” Amazon seems to feel that its current license agreements with record companies and music publishers cover the extended use they are offering in their cloud service.

When it comes to BMI, Richard Conlon, Senior Vice President, Corporate Strategy, Communications and New Media for BMI, said that Amazon had applied to BMI for a license for its cloud-locker service prior to its announcement. “Amazon has been a BMI licensee for several of its digital offerings for some time now,” says Conlon. “We look forward to negotiating a fair payment for Amazon’s transmissions of the more than 6.5 million works in the BMI catalog.”

Some believe that Amazon could sidestep the licensing issue thanks in part to the Supreme Court’s 2009 decision allowing customers of cable provider Cablevision to copy media to centralized servers provided that an existing copy remained on the users’ Cablevision-provided DVRs. However, BMI’s Conlon isn’t so sure. “The Cablevision decision is so narrowly defined that it does not directly apply to what Amazon has proposed,” he says.

When it comes to record company and publishing rights, should companies like Amazon be required to license music stored “in the cloud” that has already been legally purchased? It’s a loaded question, one worth potentially billions of dollars in long-term revenue. “This isn’t a one-dimensional issue, and the law has yet to deal much with services like Amazon’s,” observes Jacqui Cheng, senior Apple editor for technology news site Ars Technica. Hence, labels are put in the difficult position of either forcing Amazon’s hand through legal means, or, by doing nothing, “implicitly allowing other music companies to ditch cloud licenses, too,” adds Cheng.

For leading music-industry firms, this is where the rubber hits the road. Sony Music appeared less than pleased with Amazon’s brazen approach; in a statement issued through Reuters, Sony spokeswoman Liz Young said that while the company hoped to reach a licensing agreement with Amazon, “we’re keeping all of our legal options open.” Labels have been more than willing to go to the mat to protect loss of revenue at the hands of cloud-locker services; four years ago, EMI filed suit against San Diego-based music-service provider MP3tunes, asserting that its cloud locker promoted music piracy.

How It Works

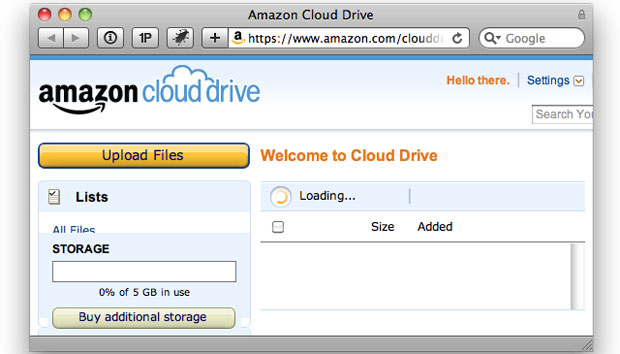

A “digital locker” hosted on the company’s servers, Amazon’s Cloud Drive is capable of storing a multitude of media files, ranging from MP3s to HD movies and more. Amazon customers are allotted a complimentary 5GB of storage to start; though users may upload any kind of purchased media, those who buy an MP3 album through Amazon are rewarded for their loyalty with a 20GB storage upgrade. Users can access stored Cloud Drive files from Amazon’s companion Cloud Player for Web page; smartphone support is provided for Android users via an Amazon MP3 app.

What makes Amazon’s service unique, says Mark Mulligan, digital-media analyst for Forrester Research, is that it requires customers to upload their music files for storage purposes, as opposed to “matching them against a cloud-based central repository of music.” Forrester’s Frank Gillett, vice president and principal analyst, says the move is a “first salvo in a series of steps that will lead Amazon to compete directly for the primary computing platform for individuals, as an online platform, as a device operating system, and as a maker of branded tablets.” The general-purpose design of the Cloud Drive, combined with the long-term opportunities for personal cloud services, suggest an interesting set of possibilities and insights into Amazon’s long-term strategy, adds Gillett.

Providing a more practical means of accessing users’ personal media libraries appears to be at the heart of Amazon’s cloud-based model. In a none-too-subtle reference to Apple’s iTunes download-and-sync methodology, Bill Carr, Amazon’s Vice President of Movies & Music, said in a statement that “customers have told us they don’t want to download music to their work computer or phones because they find it hard to move music around to different devices.”

In-the-cloud music plans (those that operate using a central network infrastructure) appear to be the next big thing for retailers jockeying for position on the increasingly crowded digital-music frontlines. Unlike traditional online services, many of these plans offer users the choice of a free, advertising-supported plan, or a premium paid-for option. By allowing users to access music through a wide range of smartphones and other connected devices, emerging providers such as Europe’s Spotify have been able to address compatibility issues, while the ability to move files to and from the cloud means that listeners need not be shackled to their home computers.

With the anticipated upcoming launch of similar cloud services for Google and Apple, all of the questions swirling around this issue will become even more important.

Community

Connect with BMI & Professional Songwriters