BMI Celebrates the Evolution of Sound

As Audio Appreciation Month comes to a close, it’s the perfect time to revisit just how far audio has traveled - from the time when sound was perceived as merely a change in air pressure to today’s digital era, in which people constantly and conveniently stream, download and share music on their mobile devices and then discuss it on different social media platforms. The transition didn’t happen overnight, of course, and the argument is never-ending over whether the actual quality of sound recording and playback is better now versus then. In the meantime, let’s take a look at some of the key stages in audio’s journey from analog to digital.

The earliest known sound recording device was patented in 1857, by way of French bookseller and printer Édouard-Léon Scott de Martinville, who was inspired by the technology used to capture light and image in photographs. Called a phonoautograph, it used a horn to collect sound waves as they passed through the air. Its major limitation was that it could not play back sound; it only collected visual images of it.

In 1877, Thomas Edison perfected Scott de Martinville’s original design from his lab in New Jersey. As explained in the book Perfecting Sound Forever: An Aural History of Recorded Music, by Greg Milner: “Edison’s voice caused a diaphragm to vibrate. This diaphragm was attached to a stylus that responded to these vibrations by etching a pattern into wax paper. This pattern was ‘analogous to’ - and therefore, an ‘analog’ of - the sound waves that caused the diaphragm to vibrate. During playback, the stylus followed that pattern, causing the diaphragm to create vibrations that re-created - shakily, but clearly enough - the original sound waves in the air.” The sound waves were then amplified by the phonograph’s horn. Edison’s phonograph, marketed by the Phonograph Sales Company, effectively became the first device to play back music. Singers in the 1920s would perform what became known as tone tests in venues large and small by singing their own recordings live in between playbacks to prove just how pure and real the audio was.

Two more phonographs of note were invented after Edison’s earliest model - the graphophone by Chichester Bell and Charles Tainter in 1885, and the gramophone by Emile Berliner in 1893. The latter used 7-inch records made of hard rubber, which could be mass-produced. In between this time, the first “jukebox” (or coin-operated cylinder phonograph) was invented. According to Steven Schoenherr of the University of San Diego, the early jukebox “earned over $1000 in its first six months of operation in San Francisco’s Palais Royal Saloon, setting off a boom in popularity for commercial nickel phonographs that kept the industry alive during the Depression.”

In 1895, Guglielmo Marconi sent and received his first radio communication in Italy, giving way to the first successful trans-Atlantic radio telegraph message some years later. There were many people involved in the invention of the radio along with Marconi, including Nikola Tesla.

The world’s first commercial AM radio station made its debut in 1920 in Pittsburgh as KDKA. During the 1920s, record sales declined as radio stations across the U.S. gained popularity. The Great Depression didn’t help matters, and it wasn’t until the late 1930s, with the advent of talkies, or talking motion pictures, that record sales recovered and gave way for better technologies, such as stereophonic recordings (as opposed to monophonic). The rise in popularity of jukeboxes also contributed to the revival in record sales.

From about 1941 to the mid 1950s, there were several technological improvements within the sound recording industry. In the U.S., the military sponsored the recording of 10-inch and 16-inch discs, largely for the entertainment of World War II troops. Throughout the 1930s and 40s, the advancements in magnetic recording technology gave way for studio tape recorders, revolutionizing the making of records and movie soundtracks.

According to the History of Recording Technology site, “in 1948 and 1949, the Victor and Columbia companies introduced the new 45-rpm disc for singles and the Long Playing record for albums (or LPs). These new high fidelity discs marked a new era in the home record player.” High fidelity equipment allowed for editing of live performances after the fact, making recording engineers critical to the recording process. Suddenly it was possible to cut a duet record with two artists who were never actually in the same room together, thanks to the wonders of mixing and editing. And mistakes made during the recording process could suddenly be erased or corrected. “In the studio, special effects and gimmicks were used freely,” cites the History of Recording Technology site. “This was also true in the new rock and roll music, where studio effects like echo and reverb became the norm. When rock entered its psychedelic phase in the late 1960s, musicians pulled out all the stops and began using every technological trick available to them to create exotic new sounds… On heavily produced records like the Beatles’ Sgt. Pepper album, the music was only remotely related to anything that could be performed live by the Beatles themselves.”

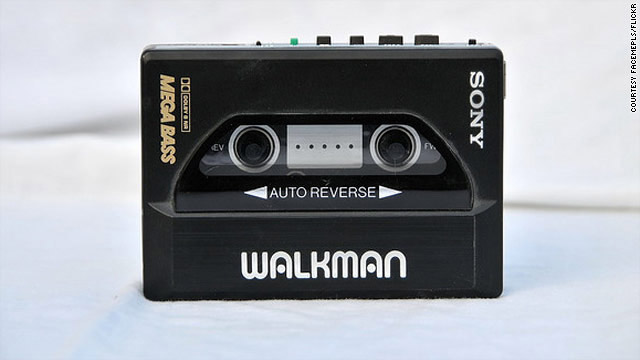

It is argued that somewhere around this time is where the “truth” of sound recordings began to get lost. In any case, in 1963, Philips made an important invention in the form of compact audio cassettes. Sony capitalized on this by creating the world’s first portable cassette player in 1979. The invention fundamentally changed how people experienced music, in the same way that Apple’s iPod mp3 player did in 2001. According to a 2009 article in Time magazine celebrating the 30-year anniversary of the Walkman, the device, first released in Japan, was an instant hit. “While Sony predicted it would only sell about 5,000 units a month, the Walkman sold upwards of 50,000 in the first two months,” the article states. “The popularity of Sony’s device - and those by brands like Aiwa, Panasonic and Toshiba who followed in Sony’s lead - helped the cassette tape outsell vinyl records for the first time in 1983.”

October 1, 1982, marked the birth of compact discs, or CDs, the first one being Billy Joel’s, 52nd Street. According to a 2012 CNN article marking the 30-year anniversary of the CD, “the first album to sell one million copies in the CD format and outsell its vinyl version was Dire Straits’ Brothers in Arms, released in 1985.” Vinyl purists argued that the grooves in the LP’s created a deeper, richer sound with more texture, a sound that was lost in newer, digital formats. The general public, however, seemed to disagree.

Sony followed up its Walkman with the release of the Discman (portable CD player) in 1988 and further capitalized on the popularity of CDs. Nowadays, even though CD sales have obviously declined, they are still holding on. According to that same CNN article, “CDs still account for the majority of album sales in the U.S. In the first half of 2012, 61 percent of all albums sold were CDs, according to the Nielsen Company and Billboard.”

When they were first introduced in the late 90s, mp3s were easily and illegally shared on peer-to-peer networks like the controversial Napster. But all that changed in 2001 when Apple released the first iPod portable music player into the market, foreshadowing the dominance of this format and allowing for music to be legitimately purchased on platforms like its iTunes music store. “Like CDs before them, this new format is changing both the creation and consumption of music,” writes CNN’s Heather Kelly in that same 2012 article. “Musicians no longer have to wait until an album is finished to release tracks - they can sell them one at a time. Length of a song isn’t an issue, just file size. Listeners have more flexibility than ever, with unlimited mix-and-match options. And increasingly, they’re opting to download single songs over albums.”

A new and interesting trend is the resurgence of vinyl among youngsters who weren’t even alive when CDs came into the picture. According to this recent New York Times article, “about a dozen pressing plants have sprouted up in the United States, along with the few that survived from the first vinyl era, and they say business is so brisk that they are working to capacity.” An extraordinary example is French electronica duo Daft Punk’s newest album, Random Access Memories. According to Nielsen SoundScan, which tracks music sales, 6 percent of the album’s first-week sales - 19,000 out of 339,000 - were on vinyl.

Still, digital consumption of music shows no signs of slowing down, as companies such as Broadcast Music, Inc. continue to advocate for and represent the rights of music creators during these changing times. If the history of sound has taught us anything, it’s that there’s always something new on the horizon.

Community

Connect with BMI & Professional Songwriters