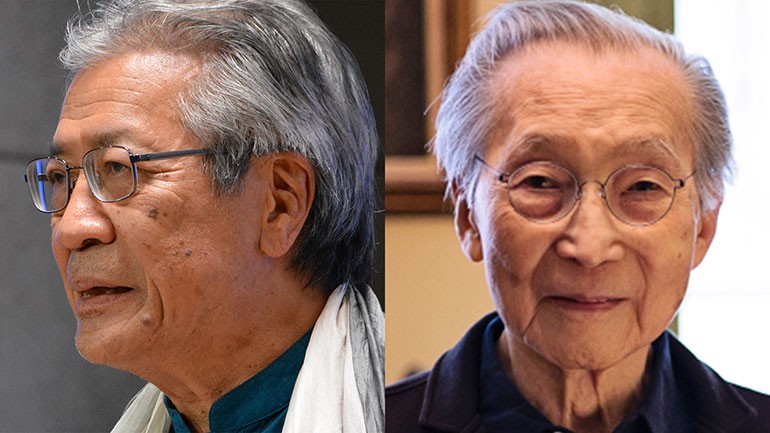

Composer Chinary Ung Pays Tribute to His Mentor Chou Wen-chung

Last year marked what would have been the 100th birthday of Chou Wen-chung. Chou came to the U.S. initially to study architecture, but dropped out to pursue his passion for music, studying with Edgard Varèse and ultimately joining the faculty of Columbia University. One of Chou’s most famous students, Cambodian-American composer Chinary Ung, has, like his mentor, made a career exploring various Asian musical practices through a Western lens. Recently, Dr. Ung shared his reflections with BMI on the wisdom gained from his late teacher, as well as how his own artistic life has flourished.

A centennial concert celebrating the music of Chou Wen-chung will be presented at Columbia University’s Miller Theatre on March 21, 2024.

How would you describe your creative process?

I don’t think about composing in terms of process. In order to master your own creativity, it’s important to be alert to all sources of inspiration, such as dreams, imagery, stories, cultural heritage, family, food, everything! Because imagination is necessary for composing, it’s important to cultivate the imagination by always being curious.

What projects are you currently working on?

Just a few weeks ago we premiered Rebirth of Apsara, an evening-length theatrical project for the Paul Dresher Ensemble featuring Cambodian traditional dancers led and choreographed by Charya Burt. I composed seven pieces for the show which invite a certain degree of improvisation.

I am now looking forward to a piece for the flute-piano duo Calliope, Elizabeth McNutt and Shannon Wettstein, who I have known for decades and who were on the faculty of my Nirmita Composers Institute in Thailand in 2017.

You studied with Dr. Chou Wen-chung at Columbia. Can you talk about what it was that drew you to him as a teacher in particular?

I first came to New York in 1964 to study clarinet at the Manhattan School of Music. I was not aware of new music at the time, but I was in the most musically vibrant city in the world, so I listened to everything I could constantly, attending concerts of all sorts of genres. At one point I found myself at a concert of Chou Wen-chung’s music. I was captivated by a piece called Cursive for flute and piano played by his pianist wife Yi-an and the flutist Sophie Sollberger. After the concert I approached Professor Chou and asked him to teach me composition. He was reluctant to do so given that I was at Manhattan, and he was teaching at Columbia, and I was so inexperienced. But I was persistent and eventually he relented, so I started taking lessons from him at his home on Sullivan Street (where his mentor Edgard Varèse had lived).

Both you and Dr. Chou have employed aspects of your respective Asian cultures in your own practice. Would you share whether Dr. Chou encouraged you towards that kind of exploration, and if so, how your approach differed from his? Has your practice evolved over time, and how?

In his essay “Sights and Sounds: Remembrances” Chou Wen-chung wrote the following:

One must search beyond the procedures of a musical practice, discern its original esthetic commitments, and trace how its tradition has evolved. If one is blessed with a cross-cultural heritage, one must then regard it as a privilege and obligation to commit oneself to the search in both practices.

I agree strongly with this statement, that it is indeed a “privilege and obligation” to have access to cross-cultural heritage and to make a sincere investment into manifesting it though creative expression. Wen-chung believed that research into one’s own culture should play a critical part in a composer’s work. My own work with Cambodian traditional music was not directly intended as part of my compositional development – at the time I was concerned with the preservation of my culture when the Khmer Rouge was murdering artists. Still, the experience of playing in a pinpeat [traditional Khmer ensemble] provided a way of listening to music that I have been able to apply to composition.

What advice do you have to share with aspiring composers?

For over 45 years I have taught young composers from around the world. No matter their background, it is always important to find out why they want to make music and to then find the spiritual space in which they can be the best creators they can be. Follow your bliss!

What role has BMI played in your career thus far?

I was first introduced to BMI around 1970 by my mentor Chou Wen-chung. Since that time, I have rarely had to concern myself with the issue of royalties and I’m very glad I don’t have to use my time to pursue such matters as it then leaves me to focus on composing. The business aspect of music is often puzzling, even in the tiny sector occupied by contemporary classical composers.

Community

Connect with BMI & Professional Songwriters